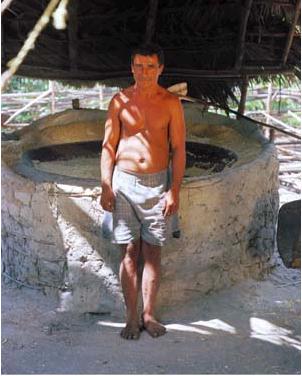

Domingos Gomes de Sousa

Dr. Jens Soentgen

Manoel Nunes

500 Jahre Mischung: Die neuen Menschen

Einführung zur Eröffnung der Ausstellung in der Alten Posthalterei in Melle

500 Jahre Mischung: Der Titel des ambitionierten Fotoprojekts von Manoel Nunes spielt auf den Jahrestag der sogenannten Entdeckung Brasiliens durch die Flotte des Pedro Cabral am 22. April 1500 an. Von Anfang an war der aus der Perspektive der Europäer neuentdeckte Kontinent Projektionsfläche utopischer Ideen. Manchmal waren sie rein materiell, oft aber auch sehr idealistisch. Eine der wichtigsten utopischen Ideen ist das Projekt "Schmelztiegel". Es geht dabei nicht nur um ein friedliches Zusammenleben der verschiedenen Rassen und Kulturen auf dem neuen Kontinent. Sondern um ein viel weiterreichendes rassenpolitisches Ziel.

Die Metapher vom Schmelztiegel

Der französische Abenteurer Michel-Guillaume Jean de Creuvecur schrieb 1782 in seinen "Letters from an American Farmer", dass in Amerika "Menschen aller Nationalitäten zu einer neuen Rasse verschmolzen werden, deren Werke und Gedeihen eines Tages grosse Änderungen in der Welt hervorrufen wird."Später lieferte der jüdische Einwanderer Israel Zangwill zu diesem Gedanken mit seinem gleichnamigen Theaterstück die passende Metapher. Zangwills Vierakter "The Melting Pot", das am 5. Oktober 1908 uraufgeführt wurde, war ein sehr grosser Erfolg, und es müssen sich ähnliche Szenen abgespielt haben, wie hierzulande bei der Uraufführung der Räuber von Schiller. Die Metapher vom Schmelztiegel verbreitete sich in Windeseile und wurde zu einem essentiellen Bestandteil des "American Dream". Die Einwanderungswelle aus Europa erreichte damals ihren Höhepunkt. Ohne Rücksicht auf Herkunft und Rasse sollten sich, so die Botschaft, in Amerika die Rassen vermischen. Die Mischung bringe einen neuen, besseren Menschen hervor. Das war die Aussage des Stückes, das inhaltlich eine Art Romeo-und-Julia-Variante war, wobei das Hindernis des Standesunterschiedes durch eine Rassendifferenz ersetzt war. Die Idee vom Melting Pot war zunächst nur auf die USA bezogen, wurde aber bald überall in der Neuen Welt populär. Vor allem in Mexiko und Brasilien fiel der Gedanke auf fruchtbaren Boden. Er hatte hier auch eher ein fundamentum in re, wiesen doch die beiden lateinamerikanischen Länder schon damals in der Tat einen wesentlich höheren Anteil an Mischlingen auf als die USA. Bald wurde der Gedanke weiter ausgeschmückt. In einem 1925 verfassten Buch mit dem Titel "La raza cosmica"1 (Die kosmische Rasse) lehrte der mexikanische Philosoph José Vasconcelos, die hohe Rassenmischung Lateinamerikas sei ein Vorgriff auf eine universelle, fünfte Rasse, die eine Synthese der schwarzen, roten, gelben und weissen Rasse darstellen solle.Die USA, die von Zangwill gelobt worden waren, verfielen in den Überlegungen des Mexikaners der Kritik: "Die Angelsachsen haben die Sünde begangen, die verschiedenen Rassen zu zerstören, während wir sie assimilieren, und dies gibt uns neue Rechte und Hoffnungen auf eine Mission ohne Vorbild in der Geschichte."

Freyres Brasilien-Utopie

In Brasilien war es kurz darauf Gilberto Freyre, der die Idee der "neuen Rasse" populär machte. Obwohl er nicht der Erfinder des Begriffs ist, hat er ihn doch wie kein zweiter verbreitet. Für Freyre ist Brasilien von vornherein das Land einer "ethnischen Demokratie". Hier habe ein Prozess der Vermischung von Europäern mit Schwarzen und Indios stattgefunden, der einen neuen, tropischen Menschentyp hervorgebracht habe, den Brasilianer. Dies war die zentrale These des 1933 eschienenen und erst 1964 ins Deutsche übersetzten Buches "Casa Grande e Senzala", "Herrenhaus und Sklavenhütte", das Freyre weltbekannt machte.

Im Mittelpunkt der Untersuchungen von "Herrenhaus und Sklavenhütte" steht das Herrenhaus einer typischen Zuckerrohrplantage im Nordosten Brasiliens. Freyre will in dieser Studie beweisen, dass nicht kirchliche oder staatliche Planung die koloniale Entwicklung bestimmten, sondern die Familien. Die brasilianische Gesellschaft entstand danach aus der Mischung dreier Rassen, die sich auf der Plantage begegnen: dem portugiesischen Kolonisator, dem afrikanischen Negersklaven und dem Indio. Für Freyre ist jeder Brasilianer geprägt von indianischem oder afrikanischem Erbe: "dieser Einfluss macht sich in unserer Zärtlichkeit, unserer übertriebenen Ausdrucksfähigkeit, unserem in Gefühlen schwelgenden Katholizismus, unserem Gang, unserer Musik und in allen unseren wesentlichen Lebensäusserungen bemerkbar. Es ist der Einfluss unserer schwarzen Kindermädchen oder Ammen, die uns in den Schlaf wiegten, die uns die Brust gaben, die uns mit dem eigenhändig bereiteten Brei fütterten. Es ist der Einfluss der alten Frau, die uns Kindern von Geistern und Tieren erzählte, des Mulattenmächens, das uns von unserem ersten 'bicho de pé' (eine Flohsorte) erlöste, das uns beim Knarren des Feldbetts die Liebe lehrte ... des Negerjungen, der unser erster Spielkamerad war."

In seinem zweiten ins Deutsche übersetzten Buch "Sobrados e Mucambos" = (wörtlich etwa: Stadthäuser und Elendsquartiere, der deutsche Titel lautet: "Das Land in der Stadt") beschreibt er den Prozess der Auflösung der alten Ordnung von Herrenhaus und Sklavenhütte. Gemeinsam mit einem weiteren Band mit dem Titel "Ordem e Progresso", der bislang noch nicht ins Deutsche übersetzt wurde, bilden diese Bücher eine Trilogie. In diesen Büchern entwirft Freyre ein Bild der brasilianischen Gesellschaft von ihren Anfängen bis zur ersten Republik. Als sein Hauptwerk gilt freilich nach wie vor die Veröffentlichung "Herrenhaus und Sklavenhütte".

Freyre glaubt, dass der zum Brasilianer gewordene Portugiese eine geschichtliche Mission habe. Die Rassenmischung betrachtete er anders als seine rassistischen Zeitgenossen nicht etwa als Verschlechterung, sondern ganz im Gegenteil gerade als Steigerung des humanitären Potentials. Portugal habe, so glaubte Freyre, eine sozusagen sanfte Kolonisierung betrieben. Und dies wiederum habe seinen Grund in dem Nationalcharakter der Portugiesen, die von Haus aus, aufgrund ihrer Lage am Rande Europas beziehungsweise zwischen Europa und Nordafrika bereits seit Jahrhunderten an den produktiven Umgang mit anderen Kulturen gewohnt waren.Die Rassenmischung, die in Brasilien stattgefunden habe, führt laut Freyre nicht etwa zu einer Gesellschaft von Untermenschen, wie es in den damals gängigen Rassentheorien (das Buch erschien im Jahr der Machtergreifung Hitlers) gelehrt wurde, sondern zu einem, wie er schreibt, neuen, besseren Menschen.Freyre benutzte das Wort von der Metarasse, und meinte, dass der Brasilianer, der eben dieser Metarasse angehört, nicht etwa etwas Schlechteres, sondern im Gegenteil eine neue Stufe der Menschwerdung darstelle. Die Rassenmischung ist ihm mehr als ein blosses Faktum, sie wird zum politischen Projekt.

"Wir Brasilianer," schreibt Freyre 1963, "arbeiten, und zwar mehr als jedes andere Volk, an der Wiedervereinigung des Menschen. Die Mischung vereinigt die Menschen, die durch Rassenmythen getrennt waren. Die Mischung vereint Gesellschaften, die durch Rassenmythen in feindliche Gruppen gespalten waren. Die Mischung reorganisiert Nationen, deren Einheit und Demokratie durch Rassenhochmut gefährdet ist. Die Mischung ist die Vollendung Christi. Die Mischung ist das Wort, das Mensch geworden ist ... Sie ist die soziale Demokratie in ihrer reinsten Form."

In solchem Predigtton wie hier hat Freyre selten geschrieben, schon gar nicht in seinen ins Deutsche übersetzten Schriften. Gleichwohl liegt auch den berühmten Büchern "Herrenhaus und Sklavenhütte" und "Das Land in der Stadt" derselbe Tenor zugrunde: Die Brasilianer sind das auserwählte Volk. Und der Mulatte ist der Üermensch. Ein Übermensch, weil er in sich mehr Kulturen vereint als andere Rassen. Bei Freyre findet die humanistische Idee vom uomo universale eine neue, überraschende Interpretation. Die Lehre war der nationalsozialistischen Doktrin von der Reinheit der Rassen diametral entgegengesetzt. Sie kehrte die Wertungen und Empfehlungen der Rassisten um: Nicht aus Kampf und Trennung erwächst das Heil, sondern aus Liebe und Vereinigung. Der portugiesische Plantagenbesitzer hätte demnach, indem er einfach seinen Neigungen folgte, die ihn zur Hütte des Sklavenmädchens zogen, bereits an einer besseren Welt mitgewirkt.

Probleme mit der multikulturellen Identität

Wenn man sich die Zahlen ansieht, so stellt man fest, dass der Bevölkerungsanteil der Mischlinge in Brasilien deutlich höher ist als in den USA, er liegt bei mindestens 40 %. Der der Weissen beträgt 54,4% (in den USA 74%), der Anteil der Schwarzen liegt bei 5,21%, der Anteil der Indios bei 0,14%. Rassenmischung ist in Brasilien also verbreitet. Viele Brasilianer haben schwarze Vorfahren. Nicht wenige erzählen von einer Indio-Grossmutter, die mit dem "Lasso im Wald" gefangen worden sei. Schon dieser Ausdruck lässt jedoch ahnen, dass die Existenz als Mischling vielleicht doch problematischer ist, als es die lächelnde Mulattin und die fröhlichen Entwürfe von Freyre, Vasconcelos und anderen ahnen lassen. Denn das Lasso deutet doch wohl hin auf Feindschaft und nackte Gewalt, auch auf Vergewaltigung. In einem berühmten Brief aus Jamaica schrieb Simon Bolivar, die Lateinamerikaner seien "weder Indianer noch Europäer .., sondern ein Mittelding zwischen den rechtmässigen Besitzern des Landes und den spanischen Usurpatoren, kurzum Amerikaner durch Geburt, aber mit Rechtsansprüchen aus Europa". Sollte die Rassenmischung am Ende vielleicht doch ein komplizierteres Geschehen sein? Das Nebeneinander von oberflächlicher Fröhlichkeit und innerem Hader fällt jedenfalls den Beobachtern immer wieder auf: "Die Menschen in Iberoamerika wissen weder, was sie sind, noch was sie sein wollen. Ihnen kommt ihre Geschichte insgesamt vor wie ein Fiasko," schrieb Jörg Kastl in der Süddeutschen Zeitung. In einem Bericht von einem Psychologen-Kongress berichtet Christine Neubaur, die Identitätsfrage sei ein konstantes Problem des mexikanischen Selbstverständnisses. Drei Typen des Umgangs mit dem eigenen Mestizentum gebe es, so fasst Neubaur die mexikanischen Diskussionen zusammen, nämlich zum einen die Verdrängung des spanischen Anteils, um sich ganz als indianisches Opfer fühlen zu können, zum anderen die Leugnung oder Marginalisierung des unterworfenen indianischen (oder negroiden) Anteils, um sich ganz zum europäischen Herrenmenschen aufwerfen zu können. Schliesslich gebe es noch die Möglichkeit, das eigene Kreolentum zynisch zu instrumentalisieren, die eigene Nichtzugehörigkeit auszunutzen in einer "Was-geht's-mich-an-Haltung", die aus der eigenen Nicht-Zugehörigkeit auf die Berechtigung zu rücksichtslosem Handeln schliessen zu können glaubt. Und wenn auch diese Typisierung etwas überpointiert erscheinen mag, so zeigt sie doch, dass die sogenannte Rassenmischung mehr Schwierigkeiten mit sich bringt, als der erste Eindruck tropischer Lebhaftigkeit vermuten lässt.

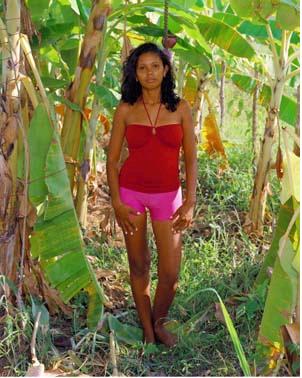

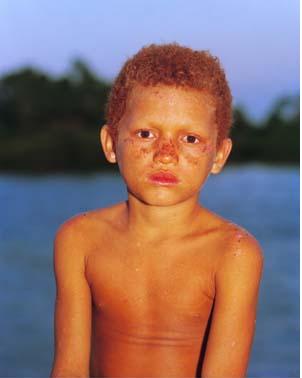

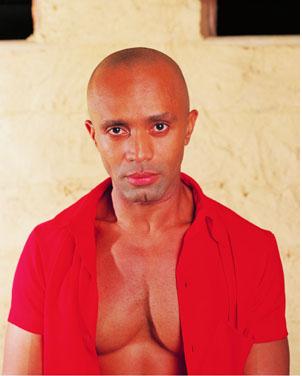

Die Fotos und die Haut

Manoel Nunes plant, die Mestigenacao in allen fünf Regionen Brasiliens zu dokumentieren - also im Nordosten, im Norden, im Südosten, im Süden und in Zentralbrasilien. Hier ausgestellt sind Arbeiten, die 1999 im Nordosten Brasiliens entstanden sind, wo Manoel Nunes geboren ist.

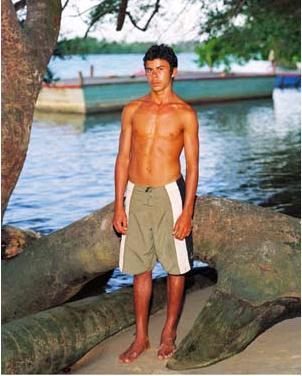

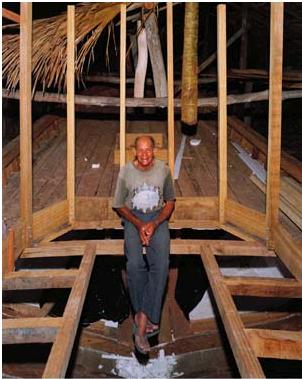

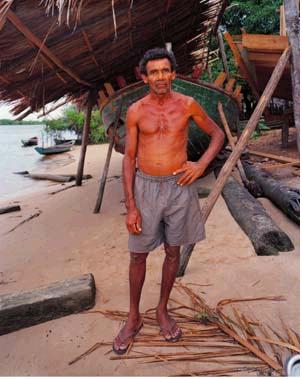

Es sind nicht die bekannten Bilder fröhlicher Mulatten, die sich unbeschwert durch multikulturelle Welt bewegen. Solche Bilder kennt man, sie werden auch in Brasilien wie ein Unterpfand der erwähnten Metarassenideologie herumgereicht. Die Leute auf den Bildern wirken vielmehr nachdenklich, verloren und oft eher traurig. Nunes arbeitet auf Grossformat, mit einer Arca Suiss, mit der etwa auch Anselm Adams seine Fotos gemacht hat. Das Grossformat ermöglicht eine wesentlich höhere Detailgenauigkeit. Ein Aspekt, der für das Projekt von entscheidender Bedeutung ist, denn man kann auf solchen Fotos, anders als auf Kleinformaten, die Haut sehen. Man erkennt feine Abstufungen in der Hautfarbe. Für jede dieser Abstufungen gibt es in Brasilien eine eigene Bezeichnung. Die Fotographien wirken, auch wenn sie oft spontan entstanden sind, meist streng durchkomponiert. Es steht eine einzige Person im Vordergrund, doch ihre Welt wird hinter ihr sichtbar.

Die Namen

Statt mit einem Titel sind die Bilder mit den Namen der Modelle bezeichnet. Das ist keine Verlegenheitslösung sondern integraler Teil des Projekts. Denn so wie das Äussere der Menschen sind auch die Namen ein Dokument der Mischung. Es gibt wohl kein anderes Land in dieser Welt, in dem so faszinierende oder auch phantastische Namen existieren wie in Brasilien. Ein Blick auf die Titel wird Ihnen zeigen, dass die Namen oft viel länger sind als wir sie hierzulande gewohnt sind. Das liegt daran, dass in brasilianischen Namen auch der Name der Mutter aufbewahrt wird, er findet sich hinter der Partikel "da", die nicht etwa einen Adelstitel anzeigt. "Araujo da Silva" setzt sich also aus dem väterlichen Bestandteil "Araujo" und dem mütterlichen Teil "Silva" zusammen. Oft lässt sich aus den Nachnamen schon die Mischung ablesen, wenn etwa ein japanischer mit einem portugiesischen Namen kombiniert ist, oder ein deutscher mit einem portugiesischen.Was die Vornamen angeht, so herrscht in Brasilien grösstmögliche Freiheit. Auf den Namensämtern reicht es,wenn man beweisen kann, dass das Wort, das man gewählt hat, gedruckt existiert. Oft wird noch nicht einmal das verlangt.Es gibt traditionelle portugiesische Namen wie Fernando Henrique oder auch französische oder italienische Namen. Nicht selten sind auchIndianernamen,wie etwa Iraja oder Irupe.Doch viele Kinder werden nach Lust und Laune benannt und heissen dann etwa Julia Yin Pin Lin, oft stehen auch Fussballhelden Pate, z.B. Beckembawer. Filmstars oder Musiker sind ebenfalls beliebt. Ich habe Leute gekannt, die Mozart mit Vorname (!) hiessen oder Wagner oder Beethoven oder auch Maikon Jackson (Mikel Jackson). In der Wissenschaft ist das nicht anders. Der Erfinder der parakonsistenten Logik heisst "Affetuoso Carneiro Newton da Costa". Manche Eltern finden es wichtig, dass alle ihre Kinder mit demselben Buchstaben anfangen, etwa mit A oder mit M. Es kommen auch reine Phantasienamen vor wie Xerox-Kopie oder sogar obszöne wie Vagina, Pimmel (Bimba) und Schlimmeres. Der Polizeichef (Delegado da Polycia Estadual) von Goiénia, wo ich ein Jahr an der Uni gearbeitet habe, hiess Hitler-Mussolini Pacheco. Niemand störte sich daran, am allerwenigsten er selbst.In der Buntheit der brasilianischen Namen tritt mehreres zutage. Zum einen Desinformation. Zum anderen aber auch eine Lust am Spiel, ja an der Travestie. Und eine unbekümmerte Haltung gegenüber der eigenen und der fremden Identität, die uns rätselhaft erscheint.Denn wie wichtig ist uns Deutschen doch unser Name, wie eifersüchtig wachen wir darüber, dass er richtig geschrieben wird! Es gibt Romane, in denen der Eigenname einer Person und seine Schreibweise ein Leitmotiv sind, etwa Mephisto von Klaus Mann. Man erkennt daran den geradezu tierischen Ernst, mit dem man hierzulande die eigene unverwechselbare Persönlichkeit gewürdigt wissen will. Eine Erbschaft des bürgerlichen Zeitalters mit seiner Hochschätzung von Selbstzucht und Selbstgestaltung.In Brasilien ist der Name eher Anlass für ein unverbindliches Spiel. Die Travestie, das Spiel mit der eigenen Identität, ist ein Kennzeichen Brasiliens. Weil der hybride genetische Hintergrund, den viele Brasilianer haben, zu einer entspannteren Haltung gegenüber sich selbst zu führen scheint.

Für Manoel Nunes verkörpert denn auch Samantha Menina mit den weissblauen Augen, deren Bild hier ausgestellt ist, die Quintessenz seines Projektes. Sie ist Transvestitin und wandert zwischen Männlich und Weiblich hin und her. Das Spiel mit der eigenen Identität ist hier zum Extrem gesteigert. Aber eine Spur Transvestitentum gehört wohl zu jedem Brasilianer.

Adelmo Silva Santos

Cornélio Evangelista da Costa

Adalberto Saldanha "Doidinho"

Raimundo Oliveira "Cada Dia"

Maria de Fátima

Luiz Oliveira

Luiz Oliveira

Maria de Fátima

Carlos Araújo de Sousa

Neguinho & Mero (Fisch)

Herondina Melo de Sousa

Manoel Gomes de Sousa

Jacimar da Conceièção "Caèçula"

Cassio de Sousa Santos "Dilinha"

Josimar Gomes da Silva "Suquinho"

Kleiton Silva

Samantha Menina